Everybody knows Apple’s maps are not as good as Google’s maps.

If somebody had belligerently stated a year ago that “Apple is not going to just walk in and be a serious player in maps,” they would have been proven right. Apple shipped their own Maps app on iOS 6, displacing the Google maps that had been a key component of the operating system since 1.0, and set the overall usability and “magic-ness” of iOS back a few notches.

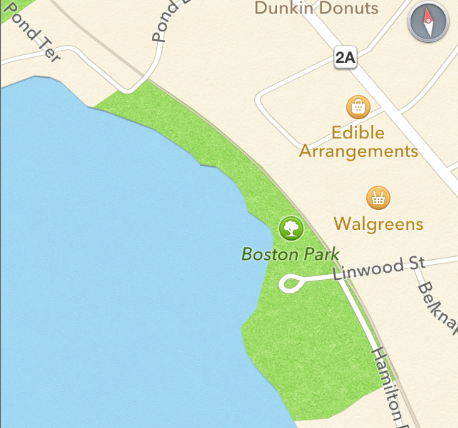

It’s all about the data. It doesn’t matter how beautiful Apple’s maps are, or how quickly they load, if they consistently assign wrong names and locations to the businesses and landmarks that customers search for on a daily basis. Here’s a map of “Spy Pond Park,” a neighborhood playground and baseball field that is central to many iPhone-toting parents’ regular routines. Inexplicably, Apple’s Maps refers to it as “Boston Park”:

Upon upgrading to iOS 6, this landmark was one of the first locations I looked up. Finding it mislabeled, I dutifully selected the “Report a Problem” option and submitted detailed correction information.

That was over 6 months ago. Today it’s still “Boston Park” on my phone. And it’s infuriating.

It’s not just “Boston Park.” My local post office shows up on the wrong side of the street. The nearest Whole Foods supermarket is purported to exist in an industrial park behind the local subway station, when it is actually located across the expressway and down the road about 1/4 mile. Other parks in my town are represented as large blank areas on the map, not locatable by name, even through trial and error.

Each of these issues is minor in isolation, but the weight in accumulation is enough to drive any sensible person to another mapping solution. If you can’t trust your Maps app to get you where you need to be, then you can’t use the Maps app. That is unfortunate, indeed.

I was among the most excited of Apple fanboys when I first heard the rumors about Apple entering the mapping market. I put my faith in Apple’s ability to zero in on the remaining nuanced usability problems in maps: the things that Google had overlooked. Instead, I learned upon updating that I had lost access to the effortless transit directions I had grown so accustomed to, and lost all faith in the accuracy of Maps’s data.

It would be foolish to expect perfection from any map, but to be a serious contender the data has to be reputable enough that mistakes are an exception rather than the rule. But more importantly for an app with such a critical impact on day-to-day living, it’s imperative that corrections to the data be as useful to the consumer as to the vendor. Currently, corrections to Apple’s Maps app are only useful to Apple, presuming they are taking them into consideration at all.

In the old days of paper maps, we expected the data to be mostly accurate, but could accommodate an occasional error. Street names change. Town borders shift. Highways are demolished and reconstructed. But in the old days, corrections were also as easy as applying pen to paper: mark out the mistake and clarify the current state of the world. One deft move and the problematic map was fixed — for the owner — forever.

I commend Apple for including the “Report a Problem” feature in their Maps app from day one. They knew that the data was not bulletproof, and they understood that their vast, loyal user base was a great resource for improving it. But I think this reporting process is failing Apple precisely because corrections to Apple’s maps lack all of the advantages of the-fashioned old pen & paper method. After laboriously detailing the problems with a point of interest in Apple’s maps, correcting its name, dragging its pinpoint to a corrected location, etc., the user is rewarded with continuing to suffer using the app with the incorrect data.

These are the most important points of data in Apple’s maps: the ones that a specific user has taken pains to refine and finesse. And Apple opts to leave them in their infuriating, sometimes dangerous state of error, making the app decreasingly useful to the customer.

I’m holding out hope that Apple is working on some major coup for the integrity of their mapping data. It would be fantastic if they announced at WWDC, for example, that they have listened to feedback from developers and customers, and are embracing some new approach to gathering and refining mapping data. Could they have something up their sleeve that would facilitate leap-frogging Google and other POI data-mongers? We can only hope.

In the absence of such improvements they should offer their users something akin to the instant fixes that were afforded by pen and paper. When I report to Apple through my own copy of Maps that the post office is in the wrong place, it should no longer be up for debate where the post office is. When I state with no uncertainty that “Boston Park” is actually called “Spy Pond Park,” I should from that point onward be able to request “directions to Spy Pond Park” without frustration.

Crowdsourcing data refinement can be a very powerful tool. Look at the success Wikipedia has had in their efforts to catalog, in a nutshell, high-level synopses of all the world’s encyclopedic data. Wikipedia works because well-intentioned contributors who spot an omission or error in the data can submit a fix and see the changes immediately. Never again (unless the change is explicitly backed out) will they be punished by reading the non-factual or incomplete information that prompted them to take action.

There are good arguments for why Apple can’t be quite as open as Wikipedia, or to choose a more apt comparison, as open as OpenStreetMap. Apple puts their brand on the iPhone because it is supposed to exude quality, and they expect to be held responsible for the quality of that product from top to bottom. Completely opening mapping data for iOS would undoubtedly lead to attempts at sabotaging Apple’s reputation by injecting embarrassingly incorrect data into the database.

On the other hand, completely botching map data in many locales, while doing little or nothing to address the problem, is also detrimental to Apple’s brand. I used to sing the praises of my iPhone above all competitors. Now, when I am jarred from my fanboy-hypnosis, staring down at an alleged life-changer that doesn’t know how to get me from point A to point B, I’m not so convinced I can defend it.

In order for Apple’s customers to continue “reporting a problem” with Maps, they need to feel that their reports are having some impact. They need to feel respected. Ideally, good reports would lead to timely corrections on a mass level that would benefit all other iOS users. Anecdotally, this is not happening. So at a minimum a user’s own report should be respected by the device they hold in their hands. Let the customer know their voice was heard by improving the usability of their device immediately. Customers demand confidence in map data, whether it be from Apple or fine-tuned by their own hand. If we can’t count on map data, we won’t use the app, we won’t report problems, and we won’t help Apple one iota in shoring up this massive shortcoming.