The macOS Mojave betas include a significant enhancement to user control over which applications can perform automation tasks. When we talk about automation on the Mac, we usually think of AppleScript or Automator, but with a broader view automation can be seen as any communication from one application to another.

One ubiquitous example of such an automation is the prevalence of “Reveal in Finder” type functionality. For example if you right-click a song file in iTunes, an option in the contextual menu allows you to reveal the file in the Finder. This is a very basic automation accomplished by sending an “Apple Event” from iTunes to the Finder.

In the macOS Mojave betas, you’ll notice that invoking such a command in an application will most likely lead to a panel asking permission from the user. The terminology used is along the lines of:

“WhateverApp” would like to control the application “Finder”.

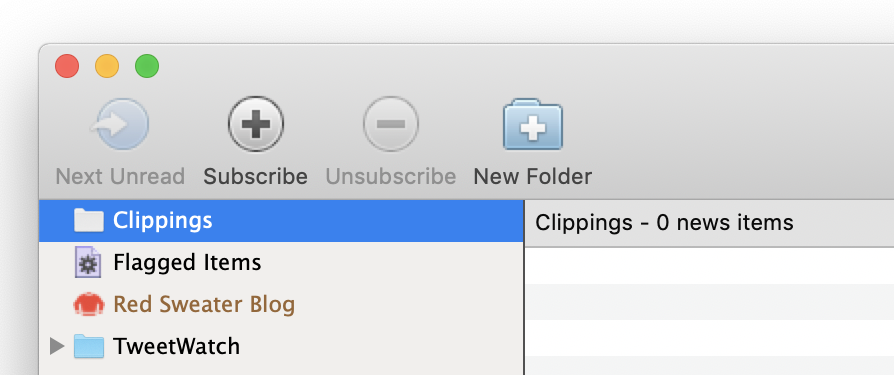

If the user selects “OK”, the application sending the command will be thereafter whitelisted, and allowed to send arbitrary events (not just the one that prompted the alert) to the Finder. If you’re running macOS Mojave you can see a list of applications you’ve already permitted in System Preferences, under “Security and Privacy,” “Privacy,” “Automation”.

These alerts are a bit annoying, but I can get behind the motivation to give users more authority over which applications are allowed to control other applications. Unfortunately, there are a number of usability issues and practical pitfalls that come as side-effects of this change. Felix Schwarz made a great analysis of many of the problems on his blog.

I ran into another usability challenge that Felix didn’t itemize: the problem of denying authorization to an application and then living to regret it. I guess at some point I must have hastily denied permission for Xcode (Apple’s software development app) to control the Finder. This resulted in a seemingly permanent impairment to Xcode’s “Show in Finder” feature. I’m often using this feature to quickly navigate from Xcode’s interface to the Finder’s view on the same files. After denying access once, the feature has the unfortunate behavior of succeeding in activating the Finder (I guess that one is whitelisted), but failing silently when it comes to revealing the file.

OK, that’s fine. I messed up. But how do I undo it? Unfortunately, the list of applications in the Security and Privacy preference pane is only of those that I have clicked “OK” for. There’s no list of the ones that I’ve denied, and no apparent option to drag in or add applications explicitly. For this high level problem, I filed Radar #42081464: “TCC needs user-facing mechanism for allowing previously denied privileges.”

What’s TCC? I’ll be darned, I don’t know what it stands for. But it’s the name of the system Apple uses for managing the system’s so-called “privacy database.” This is where these and other permissions, granted by the user, are saved. For instance, in macOS 10.13 when the system asks whether to grant access to your Address Book or Contacts, the permission is saved, and managed thereafter, by TCC.

Resetting TCC Privileges

I knew from past experience testing Contacts privileges in my own apps, that Apple supports a mechanism for resetting privileges. Unfortunately, it’s pretty crude: if you want to change the authorization setting for an application you’ve previously weighed in on, you have to universally wipe out all the privileges for all apps using a particular service. For Contacts, for example:

tccutil reset AddressBook

This completely removes the list of apps authorized to access Contacts. (The AddressBook naming is a vestige of the app’s former user-facing name.) In fact, if you type “man tccutil” from the Terminal, you’ll find that AddressBook is the only service explicitly documented by the tool. Fixing my Xcode problem is not going to happen by resetting AddressBook privileges. So what do I reset? I tried the most obvious choice, “Automation,” results in an error: “tccutil: Failed to reset database”.

What’s the service called, and does tccutil even support resetting it? After a crude search of the private TCC.framework’s binary, I discovered I was looking for “AppleEvents”:

tccutil reset AppleEvents

After running this, I quit and reopened Xcode (the TCC privileges seem to be cached), and selected “Show in Finder” on a file. Voila! The Finder was activated and I was again asked if I wanted to permit the behavior. This time, I made sure to say “OK.”

You can get a sense for the variety of services tccutil apparently supports resetting by dumping the pertinent strings from the framework:

strings /System/Library/PrivateFrameworks/TCC.framework/TCC | grep kTCCService

The list of matching strings includes names like AppleEvents and AddressBook, as well other names for things I don’t recognize, and a seemingly useful “All,” which can presumably be used to wipe out all authorizations across all services.

Because the tccutil is far more useful than is advertised, and because users are undoubtedly going to end up needing to reset services more than ever in Mojave, I also filed Radar #42081070: “Documentation and command-line help for tccutil should enumerate services.” There are some items in the dumped list that appear likely to be private to Apple, but anything genuinely useful to customers (or more likely, the consultants who fix their Macs) should be listed in the manual.

Lighten Up, Eh?

While I support the technical and user-facing changes suggested by Felix Schwarz in the previously linked blog post, some issues would be avoided by simply giving apps the benefit of the doubt for widely used, innocuous forms of automation.

I mentioned earlier that the Apple Event sent by Xcode to “activate the Finder,” was apparently whitelisted by the system. Evidently Apple saw wisdom in the thinking that simply causing another application to become active is unlikely to be widely abused. I think the same argument holds for asking the Finder to reveal a file. I filed Radar #42081629: “TCC could whitelist certain widely used, innocuous Apple Events.”

I mentioned before that I can support Apple’s effort to put more power into users’ hands with this feature, but one side-effect of requiring the authorization even for innocuous events like “Show in Finder” is that apps that do not otherwise offer automation functionality to users will nonetheless require that users grant that power.

If the merit in the feature is to allow users to limit what kinds of automation apps can perform, then supporting a “Show in Finder” feature for an application should not require me to simultaneous permit it to do whatever kind of Finder automation it chooses to. For example, an application so-authorized is now empowered, presumably, to send automation commands to the Finder that modify or delete arbitrary user files.

These days Apple always seems to be pushing the privacy and security envelope, and in many ways that is great for their users and for their platforms. With a little common-sense and some extra engineering (“It should be easy” — Hah!), we can get the best of the protection these features offer, while suffering the fewest of the downsides.